The Sawmill

Workmen and Machines

at Sturgeon’s Mill

As told by Harvey Henningsen

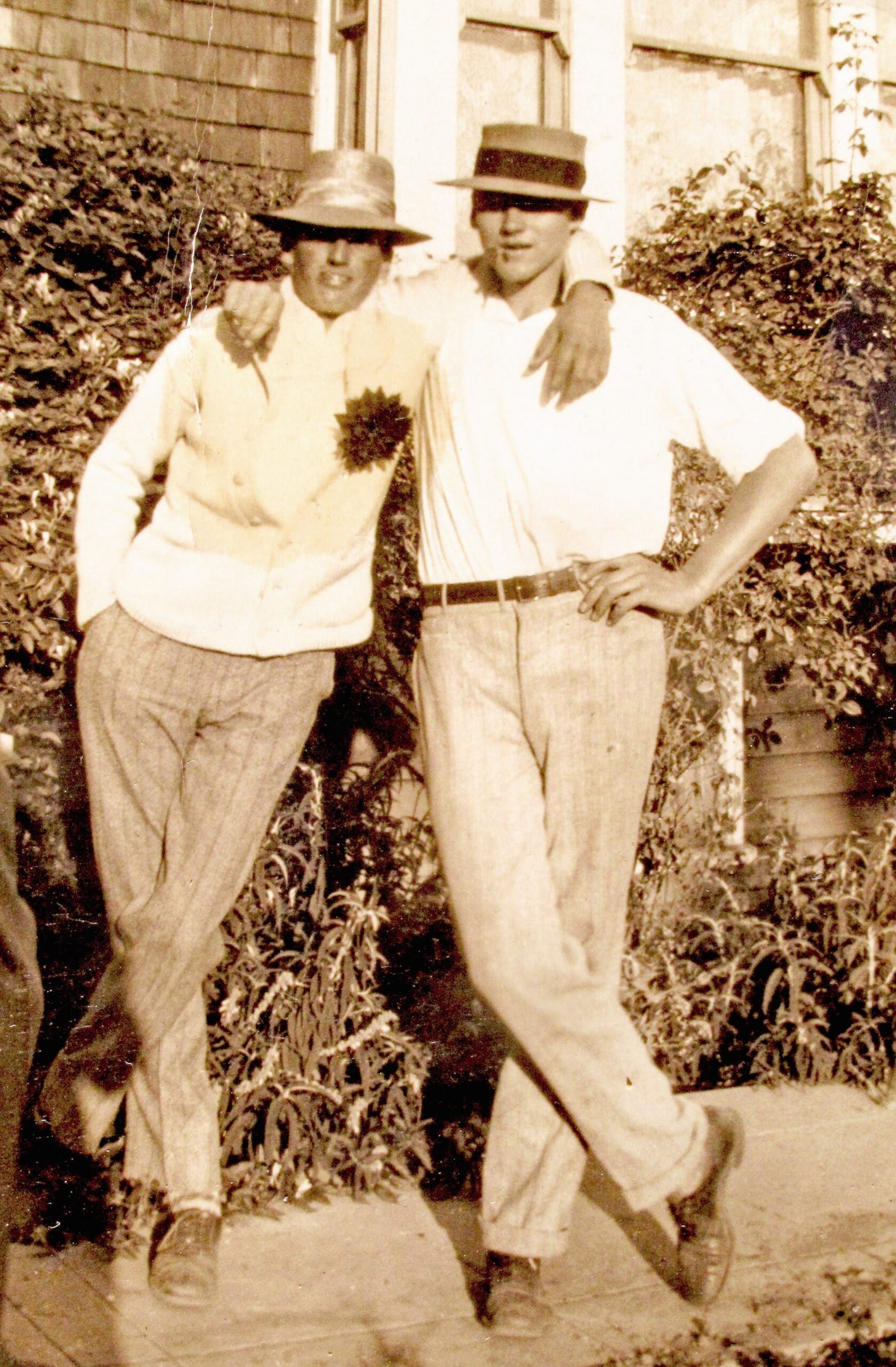

Bob Sturgeon and I, Harvey Henningsen, both grew up around this old sawmill. When we were old enough to push a broom we swept sawdust and picked up scraps of wood to throw down to Mr. Rutledge, the fireman, and engineer who worked under the mill. Bob was the mill’s block setter. I drove the little forklift and stacked lots of lumber.

When our sawmill was running at full steam, and full production there were typically 12 men staffing the sawmill. The total number of crew members including yard men and the office staff was 25 employees.

I will start describing how a sawmill works at the beginning, where the logs arrive at the mill.

The Workmen

Logs came to our sawmill on logging trucks. When I was 10-12 years old I would hitch rides with the logging truck drivers out to the logging sites (also called logging shows) and back to the mill while my Dad was working in the office. The drivers would drive their old WWII surplus logging trucks out to the Cazadero, Willow Creek, and Joy Rd. logging shows to take on their loads of logs. When the loaded logging trucks arrived at the mill they parked their trucks in front of our mill’s landing, in exactly the same spot as the picture of Jim Henningsen unloading logs. From this location, the logs were pulled off the truck one at a time with the sawmill’s mighty bull wheel, a giant winch. The earth would shake when the logs rolled off the trucks and hit the ground.

Logs came to our sawmill on logging trucks. When I was 10-12 years old I would hitch rides with the logging truck drivers out to the logging sites (also called logging shows) and back to the mill while my Dad was working in the office. The drivers would drive their old WWII surplus logging trucks out to the Cazadero, Willow Creek, and Joy Rd. logging shows to take on their loads of logs. When the loaded logging trucks arrived at the mill they parked their trucks in front of our mill’s landing, in exactly the same spot as the picture of Jim Henningsen unloading logs. From this location, the logs were pulled off the truck one at a time with the sawmill’s mighty bull wheel, a giant winch. The earth would shake when the logs rolled off the trucks and hit the ground.

Once the logs were delivered to the sawmill by the logging trucks, they had to be rolled into the mill. One crew member, the landing man was assigned to work on the mill’s landing. His job was to help unload the logs that came in during the day. Once the logs were unloaded and on the ground, his job was to look the logs over to see if there was any mud or rocks embedded in them. If there was, he washed them off with the high-pressure firehose powered by the steam-powered water pump. If the fire hose got away from the landing man it would whip all over the place like a mad snake until the steam water pump was turned off. The landing man also pulled the hook (called a Becket) attached to a heavy chain and cable out to the logs so that the mill’s bull wheel could pull the logs up to the head rig for milling. The bull wheel was operated inside the mill by another crew member. Working on the landing was a hard thankless job that made crewmen sweat.

Once the logs were delivered to the sawmill by the logging trucks, they had to be rolled into the mill. One crew member, the landing man was assigned to work on the mill’s landing. His job was to help unload the logs that came in during the day. Once the logs were unloaded and on the ground, his job was to look the logs over to see if there was any mud or rocks embedded in them. If there was, he washed them off with the high-pressure firehose powered by the steam-powered water pump. If the fire hose got away from the landing man it would whip all over the place like a mad snake until the steam water pump was turned off. The landing man also pulled the hook (called a Becket) attached to a heavy chain and cable out to the logs so that the mill’s bull wheel could pull the logs up to the head rig for milling. The bull wheel was operated inside the mill by another crew member. Working on the landing was a hard thankless job that made crewmen sweat.

This seems to be the most interesting viewing area for our visitors. It is a late 1800s Joshua Hendy head-rig that is isolated from the rest of the mill with unique angular framing built by my Pop, James Henningsen. This part of the mill contains the main saws of the mill. There is a 60” bottom, or main saw and a 44” top saw. These two giant overlapping saw blades are capable of milling lumber 54” wide. Three crew members work in this area.

The sawyer stands behind the saws and controls the levers that move the log carriage back and forth and the giant winch called the bull-wheel that pulls the logs into the sawmill and turns them on the log carriage. The sawyer controls all of the milling decisions on the first two turns of the log.

The second person that works around the head-rig is called the block setter. This crew member rides on the carriage that carries the log into the main saws. After squaring up the first two edges of the log, the block-setter takes over and controls the decisions for the rest of the milling cuts of that log.

The block-setter’s job is probably the most difficult to learn because you have to memorize different calculations for 1, 2, 3, and 4-inch thicknesses of lumber. The block-setter must look at the log as it’s being loaded onto the carriage and think like a chess player, 3 turns ahead so that the wind-check cracks in the logs are aligned in the perfect vertical position on the final cut resulting in a minimum waste of material.

The goal of milling logs into lumber from the beginning of the process to the end product is to constantly upgrade the quality of the lumber by cutting out or around imperfections such as knots, bark, rotted wood, cracks, and other flaws. This can be accomplished by deciding how wide and how long each piece of lumber will be.

The third person that works around the head-rig is the off-bearer. As the carriage passes back and forth in front of the head-rig’s main 60 and 44-inch saw blades the slabs of wood that are cut away from the log on the carriage are handled by the off-bearer. He decides whether to move the slab as a finished piece of lumber down the line and out the end of the mill or to transfer the slab to the edger and the edger-man.

The freshly cut piece of lumber at the edger is examined by the edger-man and a decision is made on what dimensions to set the edger’s four sawblades. These four saws are capable of sliding laterally on the edger’s main shaft. The edger man can change the dimensions between these blades while the machine is running. The sawblades are moved by long mechanical control arms. The edger-man looks at the rough slab of lumber and decides what multiple widths he can make out of it and sets the distance between the four saw blades accordingly.

The edger-off-bearer grabs the freshly milled multiple-width pieces of lumber as it exits the edger and transfers them back to the main rolls of the mill to be trimmed to length by the trim saw-man.

The trim saw-man and 1-2 other crew members work around this saw. The assistants throw scrap wood into the conveyor or down to the fireman or push the trimmed-to-length lumber out the end of the mill. All of the milled lumber that goes out of the mill goes by the trim-saw man. He and his assistants look at the freshly sawn lumber coming to them on the mill’s main rollers and decide what length to cut the lumber based on knots & other defects in the lumber. The lumber up-grading process is achieved here by cutting out the lumber’s defects lengthwise, making lumber at least 8 feet long plus multiple lengths of 2 feet after that. An example of this would be a 16-foot-long piece of lumber coming down the rollers, that piece of lumber can remain at full length if it has no imperfections or be trimmed to 14, 12, 10, or 8-foot lengths depending upon where the flaws in the lumber are. Scraps of lumber that could not make the grade of being salable were either cut into 2 or 4-foot lengths. The 4 footers were for the fireman down below the mill, who was also the steam engineer. The 4-foot lengths were fed into the fire-boxes below the boiler along with sawdust both providing fuel to create the heat, to create the steam, to power our six active late 1800s steam engines. The finished rough-sawn lumber went out the north end of the mill to the yard men who worked out in the lumber yard sorting, stacking, and selling lumber to the early 1900s farmers, ranchers, and general construction through the 1960s.

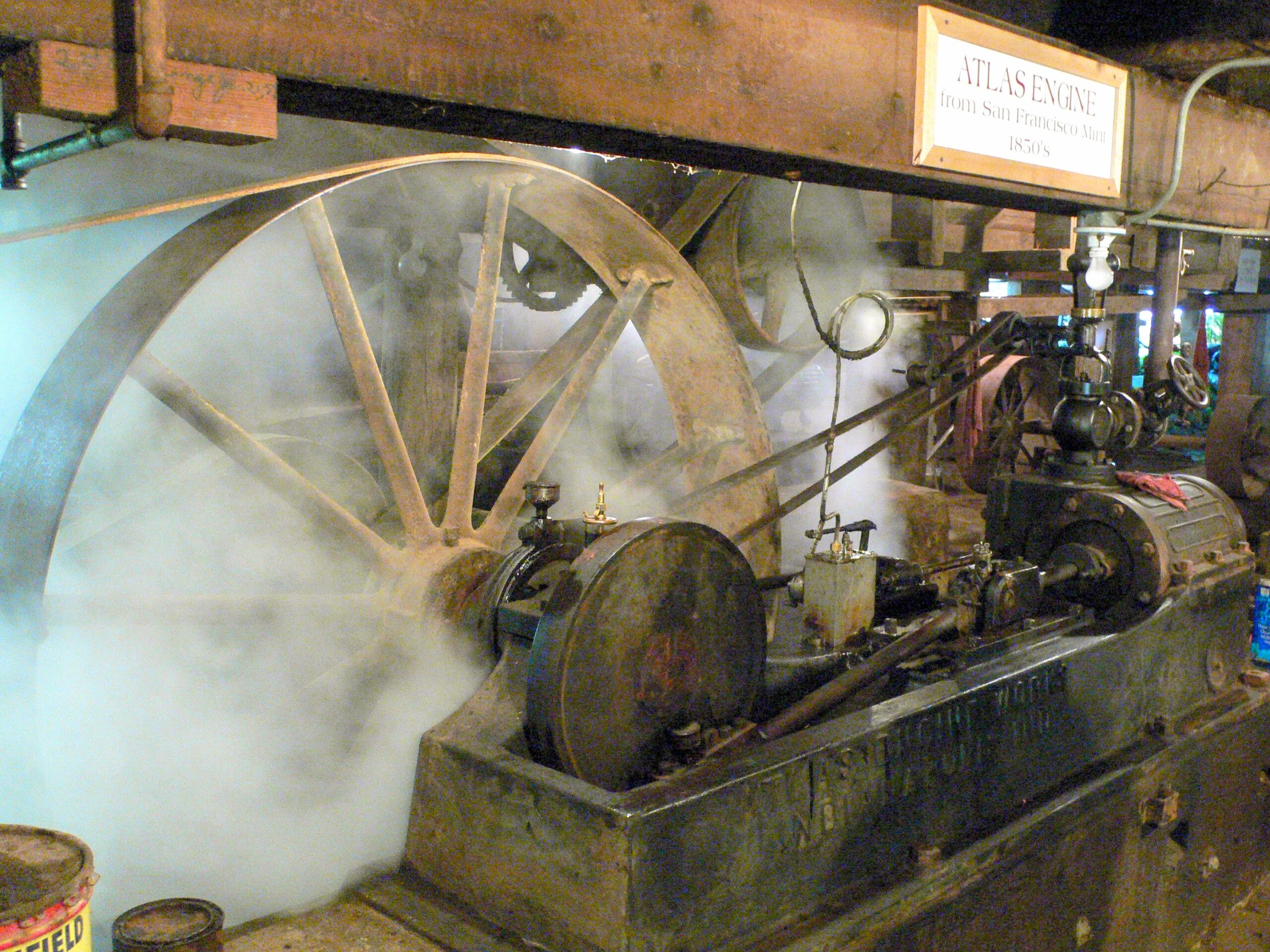

Under this sawmill are four 1800s–1900s steam engines that drive the machinery on the floor above. For every piece of equipment you see on the top floor there is a steam engine below that is powering it. Mr. Rutledge was the fireman/engineer in the 1950s. He was responsible for keeping the steam up, starting and stopping the steam engines and continuously oiling the machines. Every move he made was done with the intent of keeping the sawmill’s steam pressure up and the steam engines running at capacity. He had a heart condition and his skin color was gray as a piece of driftwood, but he kept up steam pressure for the mill. After several heart attacks, he had to leave the mill. Even though Mr. Rutledge moved slowly, every move he made counted towards creating 150 pounds of steam for all of the mill’s steam engines.

The original boiler for Sturgeon’s Mill at its present location was purchased from the Kilpatrick’s bakery in San Francisco. It was fueled with scrap wood and sawdust produced by the sawmill. The fireman/engineer operated the steam engines when given audio signals by the mill’s smaller signal whistle. The number of toots on the signal whistle communicated whether the engineer should start, stop or run slowly. The fireman shoveled a mixture of freshly cut sawdust and tossed 4-foot lengths of scrap wood from the mill into the fireboxes. The boiler is the heart of the mill as it heats water to make steam. The steam is fed to the various steam engines in the mill by big black iron steam pipes wrapped with insulation. The insulation keeps crew and visitors safe from the hot pipes and the wrapping keeps the steam hotter and more powerful for the steam engines. We are presently looking for another diesel-fired 150-horsepower boiler that will produce 150 lbs. of steam. If you know of one please contact us.

Our present active boiler is an Atlas Steam Generator. This boiler powers 5 steam engines under and around the sawmill. Our present boiler is fired automatically with diesel rather than scrap wood and sawdust to comply with air quality regulations. As a result, we no longer have a fireman, only engineers.

The Steam Engines

Atlas 1896 30 horsepower steam engine is the main steam engine of the mill, it powers the head-rig main saws, the log carriage, the hydraulic log turner, the conveyor belts, and the mill’s giant winch called the bull-wheel. The Atlas steam engine runs at 200 revolutions per minute.

Early 1900s Baker & Hamilton 5-10 horsepower steam engine that powers our trim saw. This is our smallest steam engine and was manufactured in San Francisco.

1886 Link-Belt flat-bed planer powered by a Fairbanks-Morse hit-n-miss diesel engine. Our ancient lumber planning flat-bed planer is powered by an old Fairbanks-Morse model Y hit-n-miss diesel engine. The power is transferred from engine to machine by the engine’s wheel to engage a flat belt to another receiving wheel on the shaft of the planer. The moving metal plates on the bottom of this planer transport rough-sawn lumber, up to 2 feet wide and as thick as 12 inches, under four sharp spinning knives to create a smooth planed or surfaced finish. Modern planers surface all four sides of the rough-sawn lumber at once. Our historic planer surfaces one side at a time.

Late 1800s Soule twin-cylinder steam engine that powers the edger’s lumber feed rollers. The twin-cylinder steam engines are different from any of the other steam engines in the mill because they can run in either direction and can change directions immediately from forward to reverse.

Early 1900’s Brownell and Erie steam engines. The Brownell runs occasionally as a demonstration engine and was manufactured by The Brownell Co. of Dayton Ohio. The Erie, 25 horsepower, powers the 4 saw blades on the edger and runs at 250 revolutions per minute.

Early 1900s Willamette twin-cylinder Yarder, also known as a Road Engine or Logging Donkey. These twin-cylinder engines, each with a 10 by 13-inch bore and stroke, sit side by side separated 8 feet apart by a vertical boiler, and giant cable drums and gears all bolted and riveted on I-beam steel skids. These steam engines with the huge and fascinating turning gears are outside the mill and part of the Willamette road engine demonstration located by our mill’s entrance at registration.

Demonstration Days

When you visit our sawmill on demonstration days the crew members working inside and around the mill represent the original sawmill crew. Our docents represent the mill’s yard crew that sorted and stacked the lumber coming out of the mill. They also served as the sales personnel who helped customers get the lumber they wanted.

As you watch the mill in action you will be fascinated by how our crew works together in synchronicity, almost like a ballet between men working together with their machines. Few words are spoken while they are working in the mill because, well, who can hear anything when the sawblades are working? A nod or a gesture usually communicates the next move.

As you move around Sturgeon’s Mill during your visit please don’t hesitate to ask questions to any of the docents or other crew members. They will be glad to explain the machinery and the processes of milling lumber to you.

A Typical Day at the Mill

6:00am – A typical work day for our dads, Ralph Sturgeon and Jim Henningsen, at Sturgeon’s Mill started for Ralph with a 6:00am breakfast. He would then walk from his house to the mill at 6:30am to stir up the coals in the sawmill boiler’s fireboxes that he had banked with wet sawdust the night before. Once the fires came back to life he would start adding scrap wood and sawdust to the fireboxes to slowly bring the mill’s boiler up to a working pressure of 150lbs. of steam pressure by 8:00am.

My dad, James E. Henningsen, began his day with a 6:00am breakfast. By 7:15 he would open the mill’s office and review the previous day’s lumber orders, then by 7:45 he was out in the lumber yard lining up the day’s work assignments with the 6-man yard crew.

8:00am – Two steam whistles. One long loud whistle could be heard from Graton to Sebastopol, then in two short blasts from the smaller signal whistle saying “Toot-Toot”, meaning ‘go to work’. The mill crew sawed lumber till 10:00am break time. During break time Ralph would sharpen the 60” main saw while the crew took a smoke break.

10:15am – Toot-Toot! Go to work!

12:00pm – Big Whistle…….TOOOT! Lunchtime for the crew while Ralph sharpens saws and fills oil cups and has lunch.

1:00pm – Toot-Toot! Go to work!

3:00pm – Break time. Ralph sharpens saws.

3:15pm – Toot-Toot! Go to work!

5:00pm – The mill shuts down and the crew goes home. Ralph sharpens saws, fills oil cups, unloads the last loads of logs, and yards the logs onto the log deck. He then goes to the fireboxes of the wood-fired boiler and banks the coals in the fireboxes so they’ll be ready to stir up the following morning.

6:00pm – Ralph fires up the steam-water pump and grabs the high-pressure water nozzle on the 3” canvas fire hose and washes the dirt and rocks off the logs. He then sprays water over the whole mill and surrounding grounds, protecting the mill from fire, and walks home. While James E. Henningsen locks up the mill’s office and goes home.